Adapting an Ever-Changing System

Operatic Voice Classification for the 21st Century is a multi-part series exploring the ever-changing system of voice type in classical singing through a transgender lens. The first installments delved into how types are gendered and why opera needs ungendered voice types to move forward. The final installment will draw conclusions from this and previous conversations to provide practical advice for all those involved in creating new opera.

A quick reminder that all experiences expressed here are mine and do not reflect those of transgender and/or nonbinary people in general. Everyone has their own story to tell, and this is mine.

A study of opera history quickly reveals the continually shifting nature of voice classification. We’ve phased out castrati, created distinctions such as mezzo-soprano and bass-baritone, and added modifiers to each to create the Fach system. Just as more recent classification has built upon older systems, I believe we can make tweaks to the current system to create one that’s more inclusive, descriptive, and wholly separate from binary gender identities.

Granted, we could keep classification as it is and attempt to strip the gender expectations from it. But, as I discussed in the last installment, it’s hard to change associations built into an established system. It’s worth considering changes or something entirely new, if only to allow for a more immediate adoption and implementation.

An ideal updated system would serve singers, composers, and producers. The goal is to create more flexibility for singers, a more usable tool for composers, and more detailed information for producers when it comes to casting and programming.

I encourage everyone to engage me in this conversation. My suggestions aren’t a be-all and end-all or even completely polished. I propose these next few ideas with as much openness and enthusiasm as possible. I’ve spent far too much time thinking about this and not enough time writing. I’m afraid of leaving something out, of missing an important piece of the puzzle and exposing myself to an exorbitant amount of criticism, but I’ll push forward regardless.

The way I see it, the most important elements of voice type are range, flexibility, and timbre.

Range

Obviously, the lowest and highest notes sung within a role are the basis for its type. That’s easy enough to delineate and notate. But anyone familiar with the operatic singing voice will know that there are additional factors to consider. A full lyric soprano and a coloratura mezzo may have the same range in terms of low and high notes, but how they navigate that range, and how often they’re in different parts of that range, are what differentiate their voice types and the roles written for their voices.

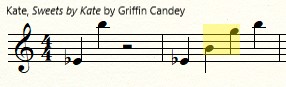

That said, I find it extremely helpful to have a range listed for each new role. At the bare minimum, that would indicate the highest and lowest notes of the role. At best, it’ll also indicate where the role generally sits and the frequency of the use of the extremes. This could be a graphic or text-based element placed at the front of the score with the role list. I’ve included a simplistic example of what could be included by the composer, using the title character of Griffin Candey’s Sweets by Kate as a model. The first measure is the role’s entire range and the second shows where the role sits most often within that range.

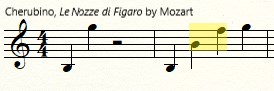

A more common example is Cherubino from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro. With the range laid out in this way, it’s easy to see why producers can choose from sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, and countertenors when casting for this role.

Another idea that I find helpful comes from my composer friend, David Howell. He thinks about repertoire ranges like an NFL draft or product recommendations: “If you sang X, you would probably also like Y.” This would be especially helpful for new operas. A singer could easily determine a role’s general fit before digging into the opera in its entirety. The implementation of this is more suited to range and flexibility than timbre, since timbre is less tied to a singer’s ability to sing a role and more dependent on a producer’s preference, the performance venue, and the instrumental ensemble available.

To continue with the example above, if you sing Kate in Sweets by Kate, you might also sing: Pamina in Die Zauberflöte (Mozart), Musetta in La Bohème (Puccini), Gretel in Hänsel und Gretel (Humperdinck), Nanetta in Falstaff (Verdi), Young Alyce in Glory Denied (Cipullo), The Rose in The Little Prince (Portman), and Helen in The Great God Pan (Crean).

Ranges could be standardized and then identified; these classifications could be as simple and clincial as numbers or as interesting as new names. Singers could exist within multiple established ranges to show their voice’s unique abilities and propensities. As I delved into in earlier installments, labels could remain as they are but without the expectation of gender, or completely new terms could be created. As a compromise, new standardized ranges could join the already-standardized types. However, I’d push for a new set of labels for ranges.

Flexibility

I define flexibility as the role’s tendency to have fast and/or moving (running or jumping) notes. The terms “coloratura” and “lyric” are currently in use for this aspect, but I believe we could be more specific.

My suggestion would be something akin to three categories: no flexibility, moderate flexibility, and high flexibility. Lyric roles would fall within both “no flexibility” and “moderate flexibility,” while most coloratura roles would be labeled “high flexibility.” For example: Countess Almaviva in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro would fall into “moderate flexibility,” but Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia would carry the “high flexibility” label. Then, the same character in John Corgliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles would be labeled with “no flexibility.”

Timbre

This is where, for me at least, things get interesting. It’s the most subjective aspect of a voice, and therefore the least helpful in creating “types.”

I think we can keep many of the Fach system’s descriptors in relation to timbre. A light lyric or a dramatic makes sense, no matter what voice type it’s modifying. It really comes down to giving names for ranges and then adding modifiers for flexibility and timbre.

An important aspect of timbre when creating new roles relates to the instrumental ensemble’s size and the density of the orchestration. The dramatic voice types emerged as the operatic orchestra changed throughout the Romantic period (and beyond) and signify a particular size in the voice. Since dramatic voices aren’t the necessary norm for new works, it would be helpful to include a size indicator within the timbre labeling system.

Timbre and Gender

Even though almost all the words we use to describe an operatic voice’s timbre (warm, steely, heavy, bright) are ungendered, timbre is where I personally find it most difficult to disentangle gender from type.

My major hang-up relates to the difference in timbre in the treble range between cisgender women and cisgender men. This most likely stems from my past as a mezzo-soprano and my tendency to listen to both cisgender women and cisgender men singing the same repertoire. There’s a quality to a cisgender man’s voice in the high treble range that immediately genders it for me.

Granted, this is a personal issue and not necessarily a systemic one. I didn’t notice my own gendering of the voice until I first heard Marijana Mijanovic’s recordings a few years ago. Her performance of Cesare (Händel) reminds me so much of a cisgender man’s voice that I had to question everything I already thought about the gendering of the physical vocal mechanism and its inherent ability to create certain sounds.

As my own voice box began to change, my concept regarding the difference between a “male” and “female” approach to shared notes diverged again. (I use quotation marks here, because, as I delve into in Part 2, gendering body parts is problematic and inaccurate.) I’d expected the change from my “female” voice box to a testosterone-affected one to be more like learning how to play the violin after playing the cello. Instead, it’s much more like giving up the cello for the trumpet.

The jarring difference makes it both easier and harder to separate my voice, and therefore all voices, from a binary gender structure. It’s harder, because it’s re-enforcing my idea that the voice-owner’s gender does affect the core sound, but it’s easier because my voice is even less binary than before. As I explained in Part 2, the voice’s gender reflects the gender of its owner, so my voice has always been nonbinary; but now that it has physically transitioned (an irreversible and finite process in the case of my voice box, but not my body), it has entered a space that far less voice boxes occupy and this fact re-enforces the need for a system that’s less reliant on gender.

One of the ultimate goals of this new system is to allow for a character’s description to determine the gender of the role, rather than the gender of the performer. This will not only free up composers and librettists to create gender-diverse characters, but it will allow more versatility in roles for all singers regardless of their gender identity and a wider range of choice for casting directors and producers.

I’ll pull this all together in the next, and final, installment of this series. In the meantime, I’d like to make a quick announcement.

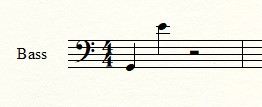

Since starting this series, my voice has changed again. I’ve left my tenor days behind me, and I’m now fully entrenched in the bass-baritone range (below). If I’ve learned anything through this process, it’s that the voice is unpredictable and incredibly unique to each person. I want to find a way to mirror that individuality in a specific, detailed, and helpful way. This series is just one step in that direction.