New Horizons, Old Barriers

In 1983, the New York Philharmonic presented two weeks of new music programming focused on a single question: “Since 1968, A New Romanticism?” The first of three major Horizons festivals, “The New Romanticism”—curated by the Philharmonic’s composer-in-residence Jacob Druckman—was a major box office hit, fueled by a wave of publicity, extensive coverage in the press, and performances of new and recent works by Druckman, David Del Tredici, John Adams, and Luciano Berio. But the significance of Horizons was not only in its examination of the emerging aesthetic trend of neo-Romanticism. Funded by the organization Meet The Composer, the festivals represented a major shift in how new music was supported in the 1980s, as composers newly embraced the orchestra, turned away from academia, and entered the classical music marketplace.

I’m currently in the midst of researching a book project that situates the Horizons festivals within the larger institutional landscape for American new music in the 1980s and early 1990s. When I presented some of my work in Bowling Green at the 2017 New Music Gathering, it centered on the relationship between Horizons and Bang on a Can, an institution that is central to my book. But for this essay, I’d like to shift focus to talk about what Horizons offered, and did not offer, as support for composers entering a new musical marketplace. My brain is a bit too full of information on this topic right now—I’ve spent most of my summer digging into archival collections related to Horizons and interviewing folks who participated in it—but I will try to make this less of an info dump and more of a critical analysis.

Meet The Composer

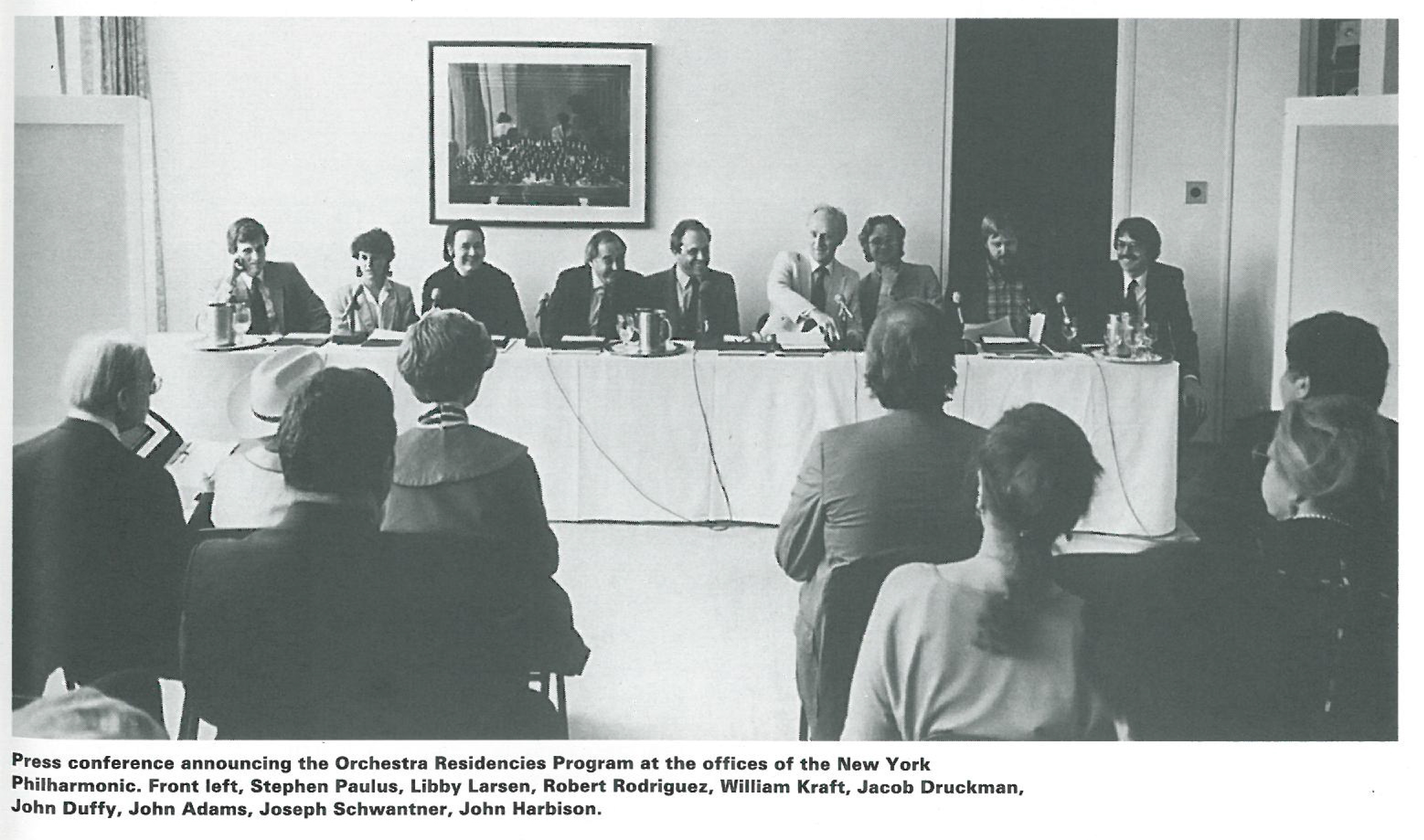

The three Horizons festivals—presented by the Philharmonic in 1983, ’84, and ’86—were a key component of one of many orchestral residencies sponsored by Meet The Composer, an advocacy and granting organization established in 1974 by composer John Duffy. Beginning in 1982, MTC established a nationwide composer-in-residence program. Modeled in part after the successful collaboration between the San Francisco Symphony and John Adams, the MTC residencies aimed to, as Duffy told EAR Magazine in 1986, create “visible ways to re-introduce and re-invigorate the whole world of the composer and orchestra.” The organization’s substantial funding was representative of the Reagan-era shifts in support for the arts: it combined public support from the NEA and state councils with foundation money from the Rockefeller Foundation, as well as corporate financing from Exxon. In comparison to the present day, MTC’s imprint was huge; in 1990, The New York Times reported that it gave on average $2.5 million to composers per year; in contemporary buying power, that is more than four times the amount of grant support that New Music USA, MTC’s successor, provides annually today.

The growing presence of MTC significantly shaped the marketplace for new music in the United States and deeply informed the idea of a non-academic “market” to begin with. One of the most startling discoveries in the course of my recent research—and this may not be casual knowledge among younger readers of NewMusicBox—is that, as recently as the 1970s, American composers frequently were not paid at all for commissions. Complaints about writing music “for exposure” were likely as common in the ’70s as they are today; orchestras often got composers to write new works simply by telling them their music would be played, not that they would be financially compensated for their efforts. As an organization, MTC argued vigorously that composers deserved to be paid. The institution’s significant fundraising and financing of the orchestral program—which included a full-time salary for resident composers—provided a more widespread understanding that a commission came with money, not just a guarantee for performance.

This notion extended into their advocacy work writ large: in 1984, MTC published “Commissioning Music,” a pamphlet for composers and patrons that included guidelines for potential commissioning fees; in 1989, the organization published a handbook titled “Composers in the Marketplace,” with basic information on copyright, performance, publishing, recordings, royalties, and promotion. Soon enough, major funding organizations were taking their cues from MTC; the New York State Council on the Arts’s 1990 program booklet based its commission fee guidelines off of research conducted by the organization. As composers entered the marketplace, MTC helped determine how much they would be paid.

Horizons and the New Romanticism

As part of his MTC residency with the Philharmonic, Jacob Druckman was selected to compose music for the orchestra, advise music director Zubin Mehta on programming, and supervise the large-scale Horizons festivals. For the first festival, he proposed “The New Romanticism,” a curatorial theme steeped in his belief that, since 1968, new music had embraced “sensuality, mystery, nostalgia, ecstasy, and transcendence.” It was a tagline from which the Philharmonic could easily benefit, as subscribers perhaps otherwise fearful of dissonant and disarming contemporary work might relax at the notion that it maintained some continuity with the 19th-century music that typically brought them to the concert hall. Indeed, one Philharmonic advertisement promised “[t]hree weeks that could just change your mind about the meaning of new music.” And a big and provocative theme like “The New Romanticism” was catnip for music critics: dozens of articles were published examining just what this new romanticism might be, and whether it represented a sea change from the academic serialism that was perceived (often stereotypically) as dominant in the world of American composition.

Over two weeks in June 1983, the Horizons festival boldly seized this moment, with six concerts of orchestral music, numerous premieres, several symposia, and a glossy program book. It was a box office phenomenon, with hundreds of people lining up outside Avery Fisher Hall to buy tickets on opening night. An internal memo in the Philharmonic archives noted that the festival “attracted a younger audience—a way of replenishing the audience” and that the success of the festival “OBLITERATES NOTION that no one cares about new music and there is no audience.”

Importantly, Horizons also offered a model for young composers to enter a new orchestral marketplace. The then 23-year-old Aaron Jay Kernis was selected by the Philharmonic to have his work dream of the morning sky read by the orchestra. In front of an audience of hundreds, Mehta took Kernis to task for his tempo markings and scoring. At one point, fed up with the criticism, Kernis apparently replied, “Just read what’s there.” The audience cheered on behalf of the composer; as the tiff was more widely reported in the press, it served as a kind of parable for the newfound power and opportunity that composers might have in the American symphonic world. An internal Philharmonic memo in the wake of the ’83 festival reports that Druckman said in a meeting that “composers now see that they can write for full orchestra and expect to be performed.”

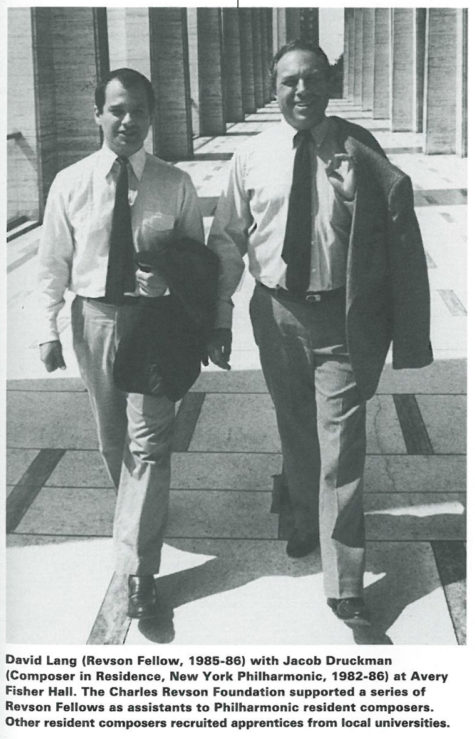

The young composers Scott Lindroth and David Lang were also hired as assistants to Druckman for preparing the ’84 and ’86 Horizons festivals, which shaped their outlooks as recent graduates from the academy. (It is not a coincidence that these composers all attended Yale, and that Druckman taught there; I’ll be addressing this connection in more detail in my book.) In a 2014 interview with me, Lindroth said of the Horizons festivals that “when composers began to realize that this too might be available to them—and that it wasn’t all about the Pierrot ensemble plus percussion—we were all very, very excited about that: there might be another way to move forward as a composer.” Horizons represented the emergence of a new kind of “middle ground”—and audience—for young composers primarily familiar with either an “uptown” world of chamber ensembles and electronic music within academia, or a “downtown” world of improvisation and DIY ensembles within alternative venues.

And although Lang was himself writing orchestral music in the mid-’80s, his takeaway from working with the Philharmonic was that this particular corner of the marketplace was not for him. He saw the orchestral world as insular and claustrophobic; as he said in a 1997 interview with Libby van Cleve as part of Yale University’s Oral History of American Music project:

It also was very demoralizing and a very good indication of how narrow the world was, and how for any composer who was saying to himself or herself, “Oh, the secret of my future will be to write one orchestra piece. Every orchestra will play it. I’ll be world famous,” it just showed how impossible, or how narrow, or how unsatisfying that experience would be.

The first Bang on a Can marathon, in 1987, was brainstormed as a direct response to Lang’s dissatisfaction with Horizons. The composer and his compatriots Michael Gordon and Julia Wolfe had spent their days in the mid-’80s hanging out at dairy restaurants on the Lower East Side, drinking coffee and complaining about institutional negligence towards contemporary work, before deciding to do something about it. But even if it seemed to offer a model for everything that the scrappy Bang on a Can would attempt to avoid, Horizons did provide new institutional connections that facilitated the upstart organization’s funding: Lang cultivated a relationship with John Duffy during his work for the Philharmonic, and MTC subsequently became the earliest major financial supporter of Bang on a Can.

The Limits of Horizons

From my vantage point today, one of the strengths of MTC under Duffy was its broad purview in terms of who was considered a composer and the resources that they thus commanded. In the 1980s, the organization’s advisory board included a significant number of female and black composers, and more diversity than many institutions today. Duffy’s strong advocacy for underrepresented voices was confirmed in my recent interview with Tania León, who served on the MTC board and worked with the Philharmonic as a new music advisor in the early ‘90s. (I haven’t gotten a chance to transcribe this interview yet, so again, stay tuned for the book.) In a 1993 questionnaire assessing MTC’s jazz commissioning program that I found during recent archival research at New Music USA, the composer and violinist Leroy Jenkins wrote of his MTC grant that “the very audacity of the idea of writing for a classical organization…has given inspiration to me and my contemporaries.” I was also struck, at a memorial service honoring Duffy in 2016 at Roulette, that Muhal Richard Abrams, a co-founder of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, performed in his honor.

But because MTC partnered with existing institutions and established composers with their own blind spots, this push for diversity did not extend into the 1983 Horizons festival. I raise this issue because, in a recent blog post about the 2017 New Music Gathering at which I presented on my research on Horizons, the composer Inti Figgis-Vizueta pointed out the absence of diversity among conference attendees and, importantly, that very few panels addressed the systemic biases that plague the world of new music today. They suggested that “there needs to be an overhaul of our ethics to require more diverse voices in new music and that starts with each participant in our gathering truly self-criticizing and understanding their own intersections of privilege and power.” As a musicologist, I believe that such an overhaul can also benefit from telling and retelling historical moments in which underrepresented voices were silenced, and in which powerful institutions were subsequently reprimanded for the same reasons they are critiqued today.

The seven orchestras that participated in the first round of MTC residencies were free to choose their own composers: all of the composers they selected were men except for Libby Larsen, who partnered with Stephen Paulus to work with the Minnesota Orchestra, and all were white except for Robert Xavier Rodriguez, who collaborated with the Dallas Symphony. Druckman was known as a non-doctrinaire figure, and the programming of the ’83 Horizons festival was impressively catholic, bringing together distinct musical styles and a wide array of composers from Del Tredici and Adams to Wuorinen and Schuller. But even as it may have included a praiseworthy “diverse” assembly of musical idioms, diversity in terms of race and gender was almost nonexistent. Only one work by a female composer, Barbara Kolb, was presented in 1983; no works by black composers were performed. This issue was raised by the singer and author Raoul Abdul, who accused the orchestra of discrimination both at the festival and in the press; in a column in the New York Amsterdam News, he wrote that “when I asked the question ‘Where are the Black Composers?’ at the opening symposium at the Library of Performing Arts last Wednesday evening, it was greeted with hisses and boos from some of the 300 people present. Philharmonic Composer-in-Residence Jacob Druckman, who put together the festival, refused to address the question directly by saying he couldn’t include everyone. He lumped Blacks in with women and other minorities.”

Understanding the fact that Horizons did not present any works by black composers in 1983 can help us understand the mechanisms that shape how and why underrepresented voices continue to be excluded in the world of new music in the present. Given the dozens of scores that were mailed to the Philharmonic by hopeful composers—the New York Public Library’s Jacob Druckman papers include many, many letters from composers submitting their work for his examination—the composer-in-residence and the orchestra certainly had access to music by African Americans, but they did not program it. And it was an issue that the organizers were aware of beforehand: when actually planning the ’83 Horizons festival, as a document in the Philharmonic archives reveals, Druckman said in a meeting that “two areas have been of concern to Meet The Composer: getting more high-power soloists; and programming a work by one of the minimalists (Reich or Glass) and by a woman or black composer.” There is much to praise in Druckman’s visionary promise of a new Romanticism and the Philharmonic’s wholehearted embrace of contemporary music with Horizons, one that might even eclipse Alan Gilbert’s worthwhile recent efforts. But declining to properly represent the diversity of the American musical landscape was one of its failures.

León mentioned in her interview with me that in the wake of the Abdul protest, Duffy marched over to the Philharmonic’s offices with a stack of scores by black composers to deliver to the orchestra. The second festival, titled “The New Romanticism—A Broader View,” addressed this injustice by including performances of music by George Lewis, George Walker, and Anthony Davis, as well as Diamanda Galás, Thea Musgrave, Laurie Spiegel, Joan La Barbara, and Betsy Jolas. But observers still pointed out the underrepresentation of women and black composers in the public forums that Horizons mounted. As reported by Johnny Reinhard in EAR Magazine, at an opening symposium for the festival in June 1984, an audience member asked of a panel of composers—which included Hans Werner Henze, Milton Babbitt, Roger Reynolds, Greg Sandow, and Druckman—“Why aren’t there any women represented here?”

“The response was an incredibly pregnant silence,” Reinhard wrote. The discussion continued to unfold awkwardly, as someone else asked, “What about Ornette Coleman?” As Reinhard described:

Mr. Sandow fielded the question by pointing out how interesting it is that Jazz musicians prefer to be kept separate from what was being represented on the Horizons series when New York Times music critic John Rockwell cried out, “That’s not true, Gregory!” It appears that Mr. Coleman had told him otherwise. “Maybe it’s because he’s black,” suggested Brooke Wentz timidly.

In 1983, a festival that embraced a new diversity of compositional idioms under the umbrella “The New Romanticism” neglected to include women and black composers. And in a subsequent festival that attempted to rectify this imbalance, a panel consisting of white male stakeholders could not fully account for the biases that those in the audience easily perceived. Meet The Composer and Horizons helped introduce composers to the marketplace, but this marketplace belonged to the institutional world of classical music, entrenched with long histories of racism and sexism that we must continue to fight against in the present day.

William Robin (@seatedovation) is an assistant professor of musicology at the University of Maryland. He completed his PhD at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with a dissertation focused on indie classical and new music in the twenty-first century United States. His research interests include American new music since the 1980s and early American hymnody. As a public musicologist, Robin contributes to the New York Times and The New Yorker, and received an ASCAP Deems Taylor/Virgil Thomson Award in 2014 for the NewMusicBox article “Shape Notes, Billings, and American Modernisms.”