The Syncopated Stylings of Charles Wuorinen

When the arguments were over, only a few famous composers younger than Milton Babbitt and Elliott Carter remained committed to old-school high modernism. Two of the best were Peter Lieberson and Charles Wuorinen. Lieberson died in 2011 at 64, Wuorinen turns 80 on June 9.

They were easy to bracket because they were friends, had a similar circle of New York City advocates, and shared something of an aesthetic trajectory inspired by the late music of Igor Stravinsky. Both Lieberson and Wuorinen had met Stravinsky in person and Vera Stravinsky asked Wuorinen to “finish” sketches from her late husband, which became his A Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky.

Stravinsky had jumped into the twelve-tone pool after the passing of his rival Arnold Schoenberg, and his last great work, Requiem Canticles, is as instantly charismatic as dodecaphony has ever been. While the early works of Lieberson and Wuorinen are relentlessly esoteric products of the hardcore Babbitt school, at some point both followed Stravinsky’s lead into comparatively accessible territory. Lieberson worked on softening the lyric line, culminating in glorious song cycles for his wife Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson, and Wuorinen took on the challenge of creating modernist composition informed by perceptible pulsating rhythm.

In his way, Wuorinen’s “perceptible pulsating rhythm” was a return to ragtime. Before Babbitt and Carter, American formal composition frequently contained the echo of Scott Joplin, a patron saint of Charles Ives, Conlon Nancarrow, George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Leonard Bernstein.

This ragtime perspective also fit with the Stravinsky influence, as Stravinsky found syncopation a natural source for his cubist phrases. Perhaps Stravinsky’s Movements for Piano and Orchestra is close to Babbitt’s rigorous discontinuity, but much else in the Stravinsky canon has a taste of ragtime, especially after he emigrated to America. Ebony Concerto (written for the Woody Herman band) is still one of best pieces in the conventional European concert idiom scored for jazz ensemble, and Stravinsky’s late non-tonal Agon (made famous by the George Balanchine ballet) is full of syncopation.

Wynton Marsalis says of The Rite of Spring: “Stravinsky turned European music over with a backbeat. Check it out. What they thought was weird and primitive was just a Negro beat on the bass drum.” If we pressed Marsalis further, he certainly would add there’s actually no “just” about that “Negro beat.” Asking musicians who are most comfortable with the European tradition to play with a groove is dicey territory. For that matter, composers themselves have seldom allowed a drummer to make up their own part.

Film composer Howard Shore had this to say about his experience trying to find an authentic “feel” for the soundtrack for Ed Wood:

Beatnik dance music—a conga player and a bongo player. At the time I recorded the score there were no studios available in Los Angeles…We ended up going to England—I recorded the score with the London Philharmonic—and it was very fortunate that we did. The British percussionists were so square, but it was the perfect sound! The bongo player was English! He was a good player and a good musician, just a little square, a little straight. In Los Angeles, they probably would have been too hip. As soon as I heard this English guy, I thought, oh, we’re so lucky to have this guy play this bongo track.

This “a little square” place is important to the soundscape of 20th-century American formal composition. It isn’t as rhythmically profound as jazz or hip hop (or another dozen American musics); it is simply basic syncopations and polyrhythms played “correctly.” The outsized pop version is found in musical theater. Leonard Bernstein is the emperor of that uninitiated energy—West Side Story is never better than when done by a college group—but a dollop of that “naive swing” has been a factor in many good performances of American concert music from Ives onward.

To bring this back to Wuorinen: the default setting of high modernism is Very Serious Indeed. Wuorinen’s post-Stravinsky “perceptible pulsating rhythm” pieces are Very Serious, but they also ask for European-style concert musicians to drive syncopations in a reasonably straight line, or at least straight enough for Wuorinen to claim they are “a hip-swinging wing-ding” (his comment on the finale to the Third Piano Concerto).

Honestly, it is as goofy as hell but remains a pleasure to listen to, especially for those who want to clear their ears out with some proper atonality once in a while. Like West Side Story, these pieces are well suited to talented college students who are reveling in their vitality: YouTube is full of smart kids nailing difficult Wuorinen scores.

For my own private 80th Wuorinen birthday celebration, I’ve been repeatedly listening to four works from the early ’80s, when he seemed to give high modernism a proper injection of “ragtime.” I imagine the composer’s smile hanging over the proceedings like a 12-tone Cheshire Cat.

The Blue Bamboula (1980)

Wuorinen has four pieces with “Bamboula” in the title. This is a tip of the hat to Scott Joplin’s notable predecessor Louis Moreau Gottschalk, who’s once-famous “Bamboula” from 1848 is a fantasy on two Creole themes.

Commissioned by Ursula Oppens, The Blue Bamboula is, in Wuorinen’s words, “A single-movement piece in which I tried to respond to Oppens’s request that the work embody the spirit of an earlier work of mine, the Grand Bamboula of 1971.” Amusingly, a quote from Tchaikovsky is fed through the modernist meat grinder. Carla Bley told Amy Beal, “To me, the piece Blue Bamboula with Garrick Ohlsson playing it, is the best piece of piano music in the world.” At one point I had a playlist of the Ohlsson and Oppens performances in rotation. Both are beautiful. (This was before the comparatively recent Molly Morkoski issue, which is also excellent.) It didn’t take long before my ears tuned up enough that I could follow the narrative smoothly: The whole work might be seen as a move from C to D-flat, and Wuorinen even gives a few repeat signs near the end.

Admittedly, if you aren’t intrigued by the style to begin with, the surface of The Blue Bamboula may still seem incoherent. It’s possible that high modernism is mostly for fellow professionals. Steve Swallow said about Carla Bley: “She has perfect pitch and can sing the notes in the voicing of incredibly dense harmonies. I’ve heard her do this to music of Charles Wuorinen, perhaps her favorite composer.”

New York Notes (1982)

Violinist Miranda Cuckson suggested I listen to this piece, which has attained the status of a classic. There are two excellent recordings. It’s common at colleges, and was one of the earliest pieces rehearsed by the important new music group eighth blackbird. For his 60th birthday it was played by the New York New Music Ensemble at the Kaye Playhouse, and for his 75th, the composer conducted it at the Guggenheim.

New York Notes refers to New York New Music Ensemble, who commissioned the work, but it is also the title of a book by celebrated New Yorker critic Whitney Balliett: New York Notes: A Journal of Jazz, 1972-1975. I doubt Wuorinen was attempting to make a connection to Balliett, but nonetheless there are many pretty jazz chords in Wuorinen’s chamber piece. Of the Wuorinen I know, New York Notes is the closest to Peter Lieberson, who was perhaps the greatest American master of sensuous, “jazzy” atonality.

Wuorinen writes, “The six members of the ensemble (flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, percussion) are all engaged in virtuoso play, but I also think of their music as comprising three duets of the related pairs of instruments, as well as six solos.” This explanation may obscure the real fun of New York Notes, which is simply that almost all fast-moving material is doubled. Usually “duets” in new music-speak means conversation and counterpoint, but not here, where “duets” literally means, “play the exact same material.”

For the first recording with New York New Music Ensemble, Daniel Druckman does a herculean job of managing all the percussion himself. On the later version with the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, there are two percussionists and a few intriguing “cadenzas” from computer generated sounds.

It might be a stretch to say that New York Notes is “grooving,” but the rhythmic excitement is palpable. The phrases are usually in obvious duples like sixteenth notes and the occasional triplet. Wuorinen told Tim Page in 1989: “From my vantage point, it is a little difficult to say what’s happened—I’ve just kept on scribbling…. [but] my use of rhythm is more periodic, more regular, more intimately related to the background pulse than it used to be—which is a long, complicated, and rather pompous way of saying that the beat is clearer.”

In New York Notes, that clearer beat powers near-vamps in the low registers and near-bebop at the top, perfect for the city of jazz, subways, and skyscrapers.

Piano Concerto No. 3 (1983)

It’s a hell of a thing. Garrick Ohlsson begins with an intense toccata that barely lets up. The percussion enters, tentatively at first, then swarming the pianist. A hypnotic slow movement gently pulses away before the coruscating finale. Like New York Notes, duples and doubling are major features: The piano plays almost the whole time and various sections of the orchestra double the piano exactly, especially in the outer movements. (This must have been a real help in rehearsal!) The language is of course atonal, but there are plenty of harmonic puns: The first movement ends with G major over D minor, the last ends with G minor over D major.

As mentioned above, Wuorinen calls the finale “a hip-swinging wing-ding.” The rhythmic excitement is perfectly judged. It’s not too square, but there’s just enough “beat” to feel propulsion.

It’s interesting to compare Peter Lieberson’s Piano Concerto played by Peter Serkin from the exact same vintage. Lieberson’s harmonies speak more naturally; they are perhaps more glamorous and “Stravinskyian” in the best sense, but Wuorinen has the syncopated edge. I have tried to listen to as many of the 20th-century piano concertos as possible, and there’s no doubt in my mind that Lieberson’s First and Wuorinen’s Third are two of the best.

These composers were producing this great music on a reasonably well-lit platform. Ohlsson and Serkin were and are two beloved pianists, accompanied on record by Seji Ozawa/Boston Symphony and Herbert Blomstedt/San Francisco Symphony respectively. Lieberson’s concerto was commissioned for the Boston Symphony centennial, Wuorinen’s piece commissioned by a consortium of five orchestras. Both works were given technically insightful rave reviews by Andrew Porter in The New Yorker.

That was then. At this point it is hard to imagine either concerto entering the general repertory, but I presume both composers were taking the long view and hoping to create music that will give at least a few people pleasure in perpetuity. The virtuosity of new music performers keeps improving (a process partially kickstarted in New York by the Group for Contemporary Music founded by Wuorinen and Harvey Sollberger in the early ’60s), and I suppose it is just barely possible that future young players will be able to put up a performance of Lieberson 1 or Wuorinen 3 as easily as Beethoven or Rachmaninoff. Time will tell. At this moment Wuorinen’s public face, a grouchy, “you kids get off my lawn” personality—a personality he seems to have had for decades, if not his whole life—has probably done harm to his status as an essential composer.

Before the performance of Brokeback Mountain this past Monday night, Miranda Cuckson quickly introduced me to Mr. Wuorinen in the foyer of Jazz at Lincoln Center. The conversation went like this:

EI: Hello! I’m a fan.

CW: (grumpy) Hello.

EI: I have the score to your Third Piano Concerto in my bag.

CW: (less grumpy) Well, that’s an antique.

EI: It seems like some of the same material is used in Spinoff.

CW: (smiling) Yes! That’s true. I totally ripped off the Concerto for Spinoff. That was the same year.

EI: Well. Thanks for all the music. You’ve written so much.

CW: (grumpy) It’s not so much. I’m 80 and there are 275 pieces. But I do work all the time.

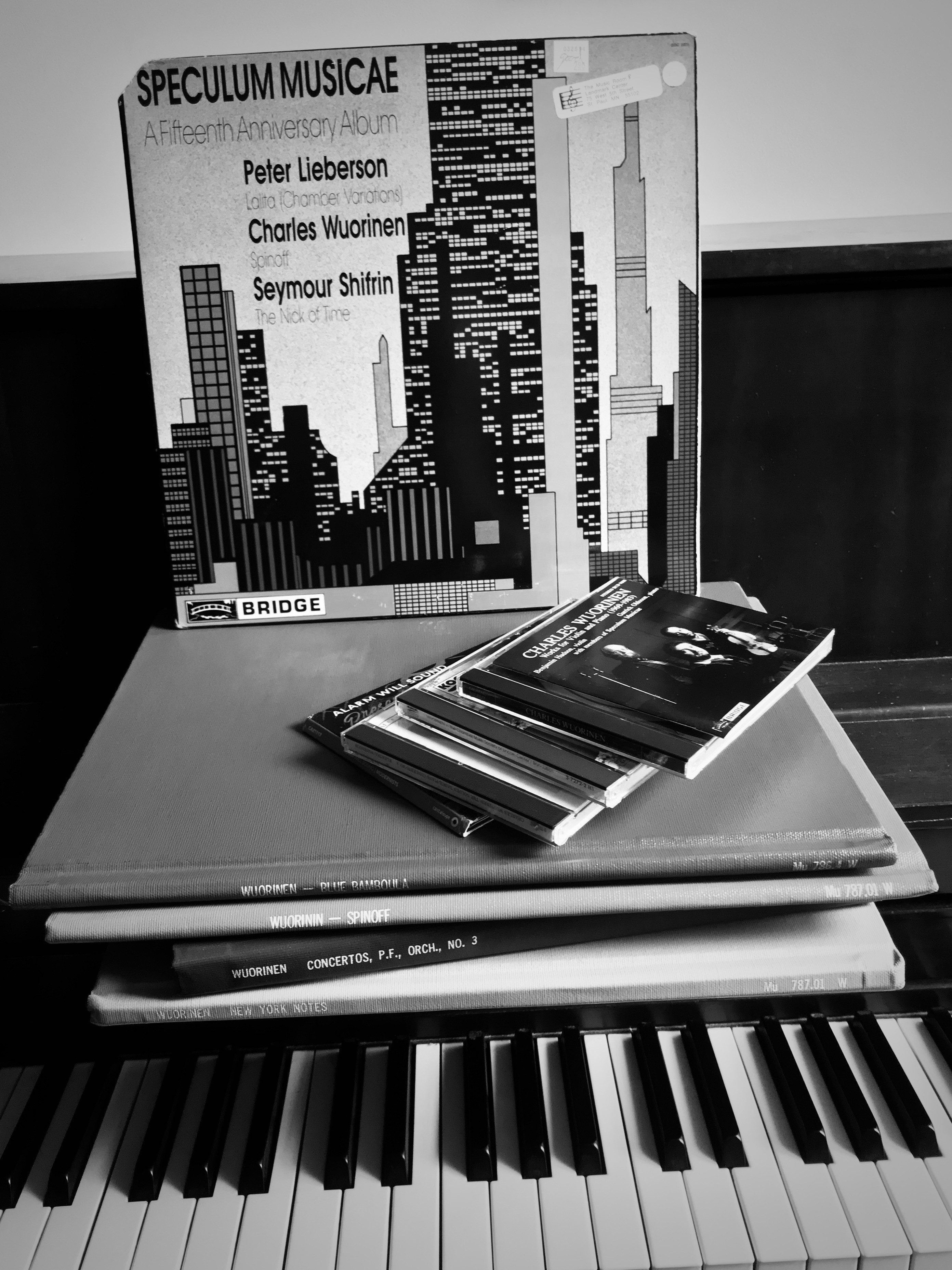

Spinoff (1983)

Patrick Zimmerli told me about this piece in 1992, so I searched out the Speculum Musicae 15th anniversary LP. Spinoff remains something I play for jazz students who are interested in combining modernist notes with pulsating rhythm. It’s only six minutes. For the first minute, the violin and bass sound like “normal” discontinuous modern music, but then Howard Shore’s beatnik conga enters and all bets are off. And, yes, a few of the lines are exactly the same as from the first movement of Piano Concerto No. 3.

It’s appropriate to compare Spinoff to another valuable item for jazz students, All Set by Milton Babbitt. Spinoff might be a bit dorky, but All Set is more dorky. If this admittedly subjective judgment is true, it’s because the beatnik conga in Spinoff holds the thread together more convincingly than Babbitt’s fragmented drum set notation for All Set.

Congas star in Spinoff, but over the years Wuorinen has written for the full percussion arsenal extensively—and well. In the liner note for his mammoth Percussion Symphony, Wuorinen says he likes drums not just for clarity, but for a “very ancient, layered set of associations, reaching well back into our distant past. Thus, modernity and antiquity are pleasingly conjoined.” Daniel Druckman (who recorded New York Notes for one percussionist) has said of Wuorinen, “He’s one of the two or three most important people for us in terms of central works and stretching the limits of what the instruments can do.” (See also Tyshawn Sorey’s note below.)

The only professional recording of Spinoff remains the first by Benjamin Hudson, Donald Palma, and Joseph Passaro. It’s good (especially from Palma, who can play jazz), but upon finally looking at the score for the first time last week, I’ve realized that some of Wuorinen’s obvious syncopations could and should be articulated more clearly.

Big Spinoff is a fun amplification of the work for Alarm Will Sound, which does justice to the “finger snapping” moments in the piece. AWS Artistic Director Alan Pierson explains, “AWS got excited about the idea of arranging it years ago. The propulsive energy and driving rhythms felt like a great match for us. We actually originally proposed doing the arrangement ourselves (Stefan Freund was gonna do it) and asked Charles’s permission. But he said he wanted to do it himself! And we love the result.”

Peter Lieberson’s note to the original LP is now hard to find. After recapping Wuorinen’s relationships to Igor and Vera Stravinsky, Lieberson offers the following observation:

Spinoff is itself replete with little homages: one cannot help but hear echoes of L’Histoire du Soldat, the music from scenes one and two, with the characteristic “breathy” rhythm of the violin against the regular pizzicati of the bass acting as a refrain throughout. The ending sounds like a pitched version of L’Histoire’s and there are other smoky echoes in the congas from Ebony Concerto. Because Wuorinen’s voice is strong and recognizably his, such homages are agreeable adornments to the direct and exuberant discourse.

If I’m arguing that Spinoff is at least a little bit goofy, there’s no way to leave out Cicadas of the Sea’s excerpt of Spinoff with vocalese and hand puppets.

I have been re-listening to early ’80s Wuorinen because I’ve kept these pieces in rotation over the last 25 years. Since then, he hasn’t given up on a syncopated style—indeed, that aspect has proven perfect for several dance commissions—but among other things there has been an abundance of vocal music and an overt engagement with early European composers like Machaut and Josquin.

At Rose Theater for Brokeback Mountain, there were several audience members in cowboy hats and jeans, apparently doing a kind of cosplay based on the hit movie. I hope they enjoyed the opera as much as I did. High modernism is a fabulous fit for the classic operatic themes of sex and death: indeed, I think opera might be the one place where a civilian can enjoy rigorous atonality as much as a professional. Unlike some reviewers, I didn’t find Brokeback overbearing or contrived. Indeed, there was a lightness in orchestration that suited the sparse set and simple story. There were even many comic moments… I mean, let’s face it, the meeting of cowboys and 12-tone music is already absurd and amusing. In the final analysis, I have only one criteria as to whether an opera is good: I need to be crying by the end, and Brokeback Mountain passed the test.

A common interpretation of Schoenberg’s Moses Und Aron is that Schoenberg thought of himself as the mute prophet Moses, offering the glories of 12-tone music to a society mostly deaf to his vision. When the lonely rancher in Brokeback Mountain swears fidelity to his dead lover, it was easy to imagine the last remaining high modernist Charles Wuorinen promising continued fealty to his beloved palette of uncompromising sounds.

Coda: With a canon as large as Wuorinen’s, it only makes sense that responses to his work will vary widely. On a hunch, I sent Tyshawn Sorey my piece and asked him if he found Wuorinen relevant. He replied:

“In my view, not only is Wuorinen totally relevant to me, but his works should be considered relevant for anyone who is interested in the study and presentment of contemporary music! Wuorinen’s music has a very direct relationship to my life in several ways. I’m mostly familiar with his 60’s and 70’s work, both as a performer and as a listener. Not so much his music from, say, the late 80’s up to now, except for New York Notes, which I really like. Since we’re discussing his 1980s music, it was also a wonderful experience preparing his Trombone Trio (1985) for performance by myself on tenor trombone and two other professors at William Paterson University from the New Jersey New Music Ensemble (a sub-group from the New Jersey Percussion Ensemble), but further opportunities to rehearse and perform the piece together fell through due to insanely crazy schedules. I’d still play that piece in a heartbeat if a pianist and percussionist would ever want to do it with me!

“But if you want to talk about the side of Wuorinen’s work I admire most, then I should mention being one of the percussionists in an exhilarating, life-changing performance of Ringing Changes (1969), a staple in contemporary music literature along with the incredible Percussion Symphony (1976), which as far as I’m concerned should be considered a ‘standard.” Even though the music itself is not nearly as rhythmically complex or discontinuous as his earlier pieces, these works are fascinating on every level—the last section of Ringing Changes featuring the tubular bells, for example, is probably some of the most beautiful music I’ve ever heard anywhere. It brought me to tears, playing the tubular bells in that section. That sound world was revolutionary for its time, and so full of life!

“It should also go without saying that I am very much in love with his earlier, more ‘rhythmically disjunct’ pieces—the ones that really did it for me were the Piano Variations, Flute Variations I & II, all of the 60s Concertos, the First Piano Sonata (Robert Miller’s performance is for me the definitive performance of this masterwork), Time’s Encomium, Arabia Felix, String Trio and the list goes on and on… And last (but certainly not least) there is my favorite composition of his, Janissary Music, which I think is one of the most virtuosic works ever to exist for one percussionist alone. The performance of this piece exemplifies a whole different kind of complexity and rigor; it’s not ‘new complexity’, and it’s not even trying to be that—it’s simply Wuorinen’s genuine compositional language. Hell, it’s new complexity done Wuorinen’s way! The percussion writing is full of extreme rigor and technical fluidity as well as some mesmerizing moments. That music truly ‘grooves’ in its own way, and doesn’t sound rhythmically ‘square’ at all! After happening upon the original CRI LP record of the piece at the William Paterson Library, I asked the genius percussionist Ray Des Roches (for whom Wuorinen composed this piece) what was it like for him to prepare this piece. He then informed me that it was so difficult to play, that it took him over a year to learn it! (This—coming from one of the most revered, pioneering figures ever to exist in the performance of contemporary music—was quite the news to hear! Des Roches’s classic recording also remains definitive!)

“I continue to listen to Wuorinen to the very present day. In fact, I was recently blasting and sort of ‘dancing’ along to one of his pieces in my car in downtown New York while waiting on a friend… folks stared, but I didn’t give a damn who was staring at me because the music excites and inspires me to move. The music is both “serious” and enjoyable, to my ears. I like to sit and read the scores, and sometimes I like to just listen and enjoy it to my heart’s content—it is totally possible to do this. Wuorinen remains a huge influence in my own work, both in terms of the rigor with which he deals with pitch selection and form, as well as the sense of melodic and rhythmic gesturing that is evidenced in all of his compositions. One of the greatest to ever do it, in my opinion!”